Primary user research means speaking to people about their past experiences and observing and analysing use of online products or services. What people say and how they behave form key parts of the evidence collected by a user researcher. However we are also very interested in what they think and how they feel. Gaining insights to a user’s thoughts and emotions can be inherently more difficult to pin down and separate out.

The focus in this article is on how to elicit, categorise and make sense of user feelings or emotions during user research. This article refers to how psychological theories of emotions can be used in a practical way during user research.

Why emotions are important?

But why do we want to know about the user’s emotions? I’d suggest there are two good reasons. The first is gaining an understanding of the emotions affecting the user because of the context or scenario they are facing when using a product or service. Every year I complete an annual tax assessment and I literally feel sick at the thought of it as it inevitably happens when my finances are at their lowest ebb. A well-designed, easy to use, easy to understand online process helps me feel in control and helps calm me down. However if the process is unclear or confusing I feel frustration and my anxiety heightens. As a user researcher it is important to understand the range of user emotions linked to the real-world task or scenario.

The second reason why it is important to understand emotions relates to the usability and impact of the product itself. In some cases the product may only work if it generates the right kinds of emotional reactions. Commercial products and services fall into this category. If use of a product or service is elective then customer loyalty will often be contingent on feelings not just usability though these two things will interact.

Collecting information about emotions during research

I use empathy maps to collate user responses from primary research. An empathy map provides spaces in which to record what users say, do, think and feel. In this example I am using a grid in Miro, I do this as the grid will automatically expand as I add more notes and it’s easy to export results for use when conducting analysis or for reporting.

I always ask user permission to record interviews with facial (video), verbal and textual transcripts for later analysis and follow a discussion guide or script written to ensure consistency across users and to stay focused on the information to be collected. Its important to plan your interventions (e.g. the questions you ask) so that you can identify the user’s emotions during the research.

In a nut-shell three problems can emerge when trying to work out how user’s feel. The first is disentangling how the user is responding to the research situation itself from their emotions in the real world. If a user appears to be nervous or uncertain is this because of the service or product being evaluated? Or are we just picking up on their reactions to the interview (and the interviewer) and what they are being asked to do? Secondly, how do we create a situation and use methods to ensure realistic emotions are elicited about the scenario or design of interest? Finally, when we have collected information about emotional responses how do we interpret it?

How do we disentangle user emotional reaction to the product or service from the research situation? I try to do three things – relax the user from the start by getting them to talk about themselves, create an environment where the user feels free to express themselves, be very clear on what you are expecting the user to do.

The key thing when creating the right conditions is to try and immerse the user as much as possible in the scenario or tasks presented to them. If the user has experience of the scenarios, the product and/or the service it may help to ask about this – though be prepared to elicit an emotional response to past events. I have conducted user research on tax and court services where users may have had upsetting real-life experiences and reminding can bring these emotions back.

Inevitably the participant cannot pretend the researcher is not there, particularly when the researcher asks pre-planned or clarifying questions or has to intervene when a participant is stuck or asks for help.

O’Brien and Wilson (2023) collated some extremely useful guidance from interviews with experienced practitioners. They suggest the following with regard to minimising and managing interventions by the researcher:

- Pre-plan questions in the discussion guide to complement the design of the tasks facing the user, think about whether an intervention will give insights which out-weigh any disruption to the flow of the session;

- Time interventions to fit in with the scenario e.g. query user expectations about the consequences of their actions or choices before they see the result;

- Don’t intervene too early if a user appears to be stuck or confused, get to the source of the confusion before offering guidance or continuing with the session, don’t assume you know why the user is having a problem!

So how do we gather information about the user’s emotions during the session itself?

- Pay attention to the user, what they are saying, the expression on their face and any non-verbal behaviours;

- Record where users behave or say things which appear to link to an emotional reaction;

- Ask them how they are feeling, but don’t overuse this intervention in the absence of other indicators!

Eliciting information about emotions

Champney & Stanney (2007) provide an approach to gaining insights to emotions linked to the user experience. They applied an emotional profiling process immediately after the interactive user ‘journey’ part of the research session. The user is asked to provide their responses to a list of positive and negative emotions potentially arising during the user experience. These are then linked to parts of the scenario or features of the product or service just experienced. The resulting emotional profile is shown as a graphical spider-plot together with a summary of the design features linked to emotional responses. The nice thing about this approach is that the practitioner can modify the process to fit in with the emotions of interest.

Another approach is to make use of software designed to recognise and interpret user emotions. Schmidt, Schlindwein, Lichtner & Wolff (2020) used off-the-shelf software to conduct three analyses of recorded usability sessions:

- text-based sentiment analysis based on transcripts of what users said where the connotations of the words used are automatically scored as to their positive or negative ‘valence’ to provide an overall ‘sentiment’ score;

- speech-based emotional analysis based on audio recordings of how users spoke which is then scored in terms of negativity v positivity;

- face-based emotional analysis using facial expressions from video recordings to identify emotional responses.

In this study little or no correlation was established between these measures of emotional response with additional usability metrics. Suggestions are provided about how to improve the use of these methods by practitioners. The lesson I took from this study is that there are additional tools available to help identify user emotions but the user researcher may have to modify processes to get the best from them.

So far we have been looking at methods for eliciting information about user emotions during the user research process. But what emotions are we looking for? To understand this we need to think about using a theory of emotions.

Using psychological theory

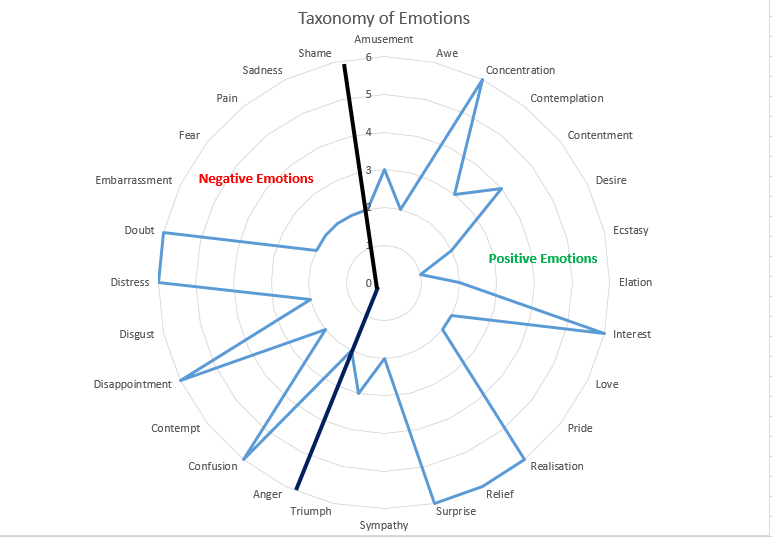

There are many theories of emotions in the psychological literature. As an example I adapted a taxonomy of emotions developed following extensive research by Cowen & Keltner (2020). I categorised the 28 emotion types they identified into broadly positive and negative emotions (some could be mixed). I then arbitrarily scored each emotion on a scale from 0 to 9 (only for illustration purposes) and awarded higher scores to several ‘positive’ emotions (concentration, contentment, interest, realisation, relief and surprise) and a selection of ‘negative’ emotions (confusion, disappointment, distress and doubt) that I would recommend starting with when evaluating user reactions to a product or service.

The wider set of emotions can also be used when considering the context or scenario that might affect users in the real world as a backdrop or reason for their use of the product or service. For example I have interviewed users of an online service used by claimants and defendants in a legal system. In this service depending on the circumstances users might already be affected by feelings of shame, fear, disgust and contempt before they start to use the service. For other types of products different ‘starting’ selections of emotions might be used depending on the design and the type of users.

User Research Guidelines

A short guide to identifying, capturing and analysing user emotions:

- Use a validated taxonomy of emotions to identify areas you might expect to encounter, including those that are design aims – build a Miro board and discuss with your stakeholders and the team;

- Build prompts into your discussion guide and mark areas of the task or scenario where you might expect to encounter or want to sample user emotions;

- Collate research results into an empathy map for each user on Miro and identify how emotions were expressed or elicited;

- Map emotions expressed by users onto the journey map you have built in Miro – look for commonalities and differences;

- If you have time consider post-user journey emotion elicitation using the approach suggested by Champney & Stanney (2007);

- If you have resources consider applying software tools to detect user emotions using post-session transcripts, audio recordings or face recordings.

References

O’Brien, L. & Wilson, S. (2023). Talking About Thinking Aloud: Perspectives from Interactive Think-Aloud Practitioners. J. User Experience, 18, 113-132.

Champney, R.K. and Stanney, K.M. (2007). Using Emotions in Usability. Proceedings of

the Human Factors and Ergonomics Society 51th Annual Meeting. Baltimore, Maryland,

October 1-5.

Schmidt, T., Schlindwein, M., Lichtner, K. & Wolff, C. (2020). Investigating the Relationship Between Emotion Recognition Software and Usability Metrics. https://doi.org/10.1515/icom-2020-0009.

Cowen, A. S., & Keltner, D. (2020). What the face displays: Mapping 28 emotions conveyed by naturalistic expression. American Psychologist, 75(3), 349–364. https://doi.org/10.1037/amp0000488